A little of Navy Seals History in VietnamIn 1962, President Kennedy established SEAL Teams ONE and TWO from the existing UDT Teams to develop a Navy Unconventional Warfare capability. The Navy SEAL Teams were designed as the maritime counterpart to the Army Special Forces “Green Berets.” They deployed immediately to Vietnam to operate in the deltas and thousands of rivers and canals in Vietnam, and effectively disrupted the enemy’s maritime lines of communication.

The SEAL Teams’ mission was to conduct counter guerilla warfare and clandestine maritime operations. Initially, SEALs advised and trained Vietnamese forces, such as the LDNN (Vietnamese SEALs). Later in the war, SEALs conducted nighttime Direct Action missions such as ambushes and raids to capture prisoners of high intelligence value.

The SEALs were so effective that the enemy named them, “the men with the green faces.” At the war’s height, eight SEAL platoons were in Vietnam on a continuing rotational basis. The last SEAL platoon departed Vietnam in 1971, and the last SEAL advisor in 1973.

Early colonial periodThe French colonized Vietnam in 1857. They made it a part of French Indochina until World War II, when it fell under Japanese rule for a short time. Vietnamese citizens rebelled during the period of Japanese rule, supported by the Communists and American OSS (Office of Strategic Services which was the pre-cursor to the CIA). A new sense of nationalism emerged amongst the Vietnamese. World War II became the catalyst for the nationalist movement, which was led by a man calling himself Ho Chi Mihn.

After the war, France returned and sought to resume control of Vietnam and other Japanese-controlled territories. As early as 1941, Indochina's Communist Party called for liberation from France. The Viet Mihn, the nationalist movement's political and military organization, under the leadership of Ho Chi Mihn, were gaining strength in the north. In 1945 Ho Chi Mihn proclaimed the Democratic Republic of Viet Nam and right for the Vietnamese to rule themselves. Their Declaration of Independence was written to be similar to the United States Declaration of Independence of 1776, hoping to gain support and sympathy from their one-time ally, America.

Elections that followed were strongly in favor of the Viet Mihn position. Ho Chi Mihn was proclaimed President of the new Republic and he demanded the immediate withdrawal of the French and complete independence for Vietnam. Ho Chi Mihn made these demands, relying on the support and aid he was receiving from two important sources: the Communist Chinese, and the American OSS Teams. The Communist Chinese trained the Viet Mihn and fought with them against the Japanese. The American OSS was advising Ho Chi Mihn in their common struggle against the Japanese. The United States government realized that the Viet Mihn was an effective fighting force and Ho Chi Mihn's organization was the only stable leadership in Vietnam.

With the Chinese and OSS supporting Ho Chi Mihn, France found it difficult to oppose his new Republic. By late 1945, the OSS Teams were finally withdrawn and the French agreed to recognize the Democratic Republic of Viet Nam as long as it remained part of France. The French also agreed that if some time in the future the country wanted to unite under Ho Chi Mihn, France would submit to the decision of the people.

However, negotiations failed when neither side was willing to make any real compromise. Armed confrontations began between French Troops and the Viet Mihn, now called the National Front. The country of Vietnam divided: Ho Chi Mihn consolidated to the north in Hanoi, while the French set up government and command in the south at Saigon.

The French, with their Vietnamese allies, fought against the Viet Mihn from 1946 to 1953. This war consisted mostly of guerrilla actions, leaving neither side with a clear advantage. France's military policy was not effective against guerrilla tactics, and the best the French could do was to hold the primary populated areas and main lines of communication, hoping to draw the Viet Mihn into a major action. The French were suffering heavy losses and casualties and needed a major win. They believed that if they were to get the Viet Mihn onto a conventional field of battle, France would have the upper hand.

The trap was set in a small valley in northwestern Vietnam, which was believed to be a guerrilla power base, about 150 miles west of Hanoi and 25 miles from the Laotian border. Under the control of General Henri Navarre, the French troops planned to lure the Viet Mihn into battle with a large airborne assault force, which would secure the valley and establish a fortification around the deserted airfield there. When the Viet Mihn attacked, the French would destroy them.

Dien Bien Phu became one of the greatest post-WWII battles. The French were defeated at Dien Bien Phu because they greatly underestimated the determination and abilities of the Vietnamese guerrilla forces. The French fortifications were insufficient; they were out manned, outgunned, and outmaneuvered. Neither the bravery of the French troops, nor the legendary heroics of the French Foreign Legion paratroopers, were enough to save the situation. This defeat shocked the French people and their government, eliminating their will to continue the war.

In July 1954, talks between France and the new Republic, held in Geneva, finally produced an agreement. The Geneva Agreement ended colonial rule in Vietnam with a working plan for the smooth transition of power from the French to the Vietnamese. The agreement divided Indochina into four parts: Laos, Cambodia, and North and South Vietnam. The ardently Communist Viet Mihn, lead by Ho Chi Mihn, ruled the North, while the French assisted in the establishment of an anti-communist Vietnamese government in the South, headed by Emperor Bao Dai.

With the northern region being the industrial center, and the southern regions being agricultural, the division of Vietnam posed economic problems. This division also caused a major shift in population. The large Catholic population in the North, fearing retaliation from the new Communist regime for their support of the French began an exodus to the South. An estimated 100,000 of the Viet Mihn stationed throughout the South, by order of the Hanoi government, began their own exodus to the North. However, at least 5,000 of their ranks remained behind, joining the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam to form the Viet Cong (VC). They lived in the South Vietnamese villages and fought against the American-funded ARVN (Army of the Republic of Viet Nam) and American troops.

Ho Chi Mihn was confident that he would win the elections, and turned his attention toward the economic and social troubles facing his government. He realized that the U.S. might aid the South in its establishment, but he did not foresee that South Vietnam would find grounds to cancel the elections. The Americans supported the Premier of South Vietnam, Ngo Dihn Diem, who replaced the self-exiled Bao Dai. Ngo Dihn Diem gradually increased his sphere of power, while the United States began to assume the role of supporter left vacant by the French.

America gets involvedCambodia was the only state involved which refused to sign the Geneva Agreement; it was self-declared neutral and led by Prince Norodom Sihanouk.

Although Cambodia tried to play all sides against one another, the war didn't lead into Cambodia until later years Laos, whose leader was Prince Souvanna Phouma, tried to develop a neutralist coalition government of both pro-Western and pro- Communist supporters. Prince Phouma's half-brother Prince Souphanouvoing headed the Communist faction, called the Pathet Lao. Prince Boun Oum had the support of the 25,000-man Royal Laotian Army (RLA); the RLA led the pro-Western faction, and the United States Government supported it in order to counter a growing Communist presence in Asia.

Each faction actively tried to gain an advantage in the government. The 1958 elections gave the Pathet Lao more votes and the U.S. put pressure on Souvanna Phouma to resign in favor of the American-backed, Phoui Sananikone, who would continue the neutralist policy. This support from the United States was offensive to many. A young captain, Kong Le, who commanded the paratroop battalion of the RLA, seized the Laos capital, Vientiane, demanding a return to the neutralist policies.

The Soviet Union began sending arms, vehicles, and antiaircraft to Kong Le's forces, while the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) sent cadres to train the troops of the Pathet Lao.

Due to the landlocked position of Loas, to gain any advantage American troops would have to be committed and the supply problems were too great. The United States abandoned Laos and turned its support of arms and military aid, including aircraft and Special Forces Advisors, to South Vietnam.

At the end of the 1950s, there were few Special Operations Forces. The Army had the Green Berets, and the Navy had their Underwater Demolition Teams (UDT). These elite units were trained to fight and operate behind the lines of a conventional war, specifically in the event of a Russian drive through Europe.

The Navy entered the Vietnam conflict in 1960, when the UDTs delivered small watercraft far up the Mekong River into Laos. In 1961, Naval Advisers started training the Vietnamese UDT. These men were called the Lien Doc Nguoi Nhia (LDNN), roughly translated as the "soldiers that fight under the sea."

President Kennedy, aware of the situations in Southeast Asia, recognized the need for unconventional warfare and utilized Special Operations as a measure against guerrilla activity. In a speech to Congress in May 1961, Kennedy shared his deep respect of the Green Berets. He announced the government's plan to put a man on the moon, and, in the same speech, allocated over one hundred million dollars toward the strengthening of the Special Forces in order to expand the strength of the American conventional forces.

Realizing the administration's favor of the Army's Green Berets, the Navy needed to determine its role within the Special Forces arena. In March of 1961, the Chief of Naval Operations recommended the establishment of guerrilla and counter-guerrilla units. These units would be able to operate from sea, air or land. This was the beginning the official Navy SEALs. Many SEAL members came from the Navy's UDT units, who had already gained experience in commando warfare in Korea; however, the UDTs were still necessary to the Navy's amphibious force.

The first two teams were on opposite coasts: Team Two in Little Creek, Virginia and Team ONE in Coronado, California. The men of the newly formed SEAL Teams were educated in such unconventional areas as hand-to-hand combat, high altitude parachuting, safecracking, demolitions and languages. Among the varied tools and weapons required by the Teams was the AR-15 assault rifle, a new design that evolved into today's M-16. The SEAL's attended UDT Replacement training and they spent some time cutting their teeth at a UDT Team. Upon making it to a SEAL Team, they would undergo a three-month SEAL Basic Indoctrination (SBI) training class at Camp Kerry in the Cuyamaca Mountains. After SBI training class, they would enter a platoon and train in platoon tactics (especially for the conflict in Vietnam).

The Pacific Command recognized Vietnam as a potential hot spot for conventional forces. In the beginning of 1962, the UDT started hydrographic surveys and Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV) was formed. In March of 1962, SEALs were deployed to Vietnam for the purpose of training South Vietnamese commandos in the same methods they were trained themselves.

In February 1963, operating from USS Weiss, a Naval Hydrographic recon unit from UDT 12 started surveying just south of Da Nang. From the beginning they encountered sniper fire and on 25 March were attacked. The unit managed to escape without any injuries, the survey was considered complete and the Weiss returned to Subic Bay.

By 1963, the Vietnamese LDNN was starting to meet success within their missions. Operating American-provided, Norwegian-built "Nasty" class fast patrol boats out of Da Nang, the LDNN were able to make several raids against North Vietnamese targets. On 31 July, the Nastys were used on a mission to destroy a radio transmitter on the island of Hon Nieu. Using 88mm mortar on the night of 3 August, they shelled the radar site at Cape Vinh Son.

Due to the immense firepower of the 88mm recoilless, the North Vietnamese believed the large guns of an U.S. Naval ship were bombarding them. Under this assumption, NVA gunboats made a daylight attack on the USS Maddox, which was cruising off the North Vietnamese coastline, intercepting radio transmissions. This and a second attack later the same day on the USS Turner Joy came to be known as The Gulf of Tonkin Incident.

The Gulf of Tonkin Incident gave the Unites States the legal and political power to justify a stronger involvement in the Vietnam conflict. A bombing of an U.S. Air Base on 30 October 1964 killed five servicemen. Another attack on Christmas Eve hit a U.S. billet in Saigon, killing 2 servicemen. President Lyndon Johnson ordered "tit-for-tat" reprisal: for every attack from the North Vietnamese, American troops would respond in the same manner. The initiation of Operation "Flaming Dart," which included the American bombing of targets in North Vietnam, placed America in the middle of an all out war.

The CIA began SEAL covert operations in early 1963. At the outset of the war, operations consisted of ambushing supply movements and locating and capturing North Vietnamese officers. Due to poor intelligence information, these operations were not very successful. When the SEALs were given the resources to develop their own intelligence, the information became much more timely and reliable. The SEALs and Special Operations in general started showing an immense success rate, earning their members a great number of citations.

Between 1965 and 1972, there were 46 SEALs killed in Vietnam. On 28 October 1965, Comdr. Robert J. Fay was the first SEAL killed in Vietnam by a mortar round. The first SEAL killed engaged in active combat was Radarman second-class Billy Machen who was killed in a firefight on 16 August 1966. Machen's body was retrieved with the help of fire support from two helicopters, after the team was ambushed during a daylight patrol. Machen's death was a hard reality for the SEAL teams.

The SEALs were initially deployed in and around Da Nang, training the South in combat diving, demolitions and guerrilla/anti-guerrilla tactics. As the war continued, the SEALs found themselves positioned in the Rung Sat Special Zone where they were to disrupt the enemy supply and troop movements, and into the Mecong Delta to fulfill riverine (fighting on the inland waterways) operations.

The brown water of the Delta provided the foundation for the development of SEAL riverine operations. The SEALs adapted quickly and with deadly results. The braces, inlets and estuaries intermingled and left a broad area for both the North and South to operate. The SEALs and Brown Water Navy Boat Crews made it their job to win this part of the war, impeding as much as possible the movement of troops and supplies coming from the North.

The SEAL teams experienced this war like no others. Combat with the VC was very close and personal. Unlike the conventional warfare methods of firing artillery into a coordinate location, or dropping bombs from thirty thousand feet, the SEALs operated within inches of their targets. SEALs had to kill at short range and respond without hesitation or be killed. Into the late sixties, the SEALs made great headway with this new style of warfare. Theirs were the most effective anti-guerrilla and guerrilla actions in the war.

However, back at home the politics of war were working against the administration. The anti-war protest became much louder by the end of the sixties. The American public began to question this war that was claiming so many of their young men. The anxiety and anger caused by the war began to take its toll and violence erupted at home. National Guard units were sent to college campuses to disperse protesters. The now infamous incident at Kent State that resulted in four fatalities was one of many clashes between protesters and the government.

SEALs continued to make forays into North Vietnam and Loas, and unofficially into Cambodia, controlled by the Studies and Observations Group. The SEALs from Team 2 started a unique deployment of SEAL team members working alone with South Vietnamese Commandos. In 1967, a SEAL unit named Detachment Bravo (Det Bravo) was formed to operate these mixed US/ARVN units, which were called South Vietnamese Provincial Reconnaissance Units (PRU).

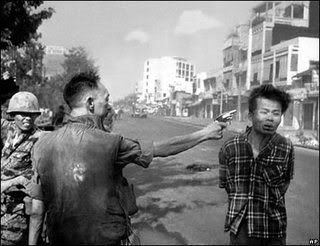

In the beginning of 1968, the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong orchestrated a major offensive against South Vietnam. Virtually every major city felt the effects of the "Tet Offensive." The North hoped it would prove to be America's Dien Bien Phu. They wanted to break the American public's desire to continue the war. As propaganda the Tet Offensive was successful: America was weary of a war that could not be won, for principles no one was sure of. However, North Vietnam suffered tremendous casualties, and from a purely military standpoint the Tet Offensive was a major disaster to the Communists.

By 1970, the US decided to remove itself from the conflict. Nixon initiated a Plan of Vietnamization, which would return the responsibility of defense back to the South Vietnamese. Conventional forces were being withdrawn, however, operations of the SEALs continued. The SEALS had developed a new base at the tip of the Ca Mau Peninsula and created a floating firebase, now known as Seafloat, by welding together fourteen barges. Accessible from sea, it also provided a landing area for helos.

On 6 June 1972, Lt. Melvin S. Dry was killed when entering the water after jumping from a helicopter at least 35-feet above the surface. Part of an aborted SDV operation to retrieve Prisoners of War, Lt. Dry was the last Navy SEAL killed in the Vietnam conflict. The last SEAL platoon departed Vietnam on 7 December 1971. The last SEAL advisor left Vietnam in March 1973.

source:

www.navyseals.com/navy-seal-history?page=0%2C1